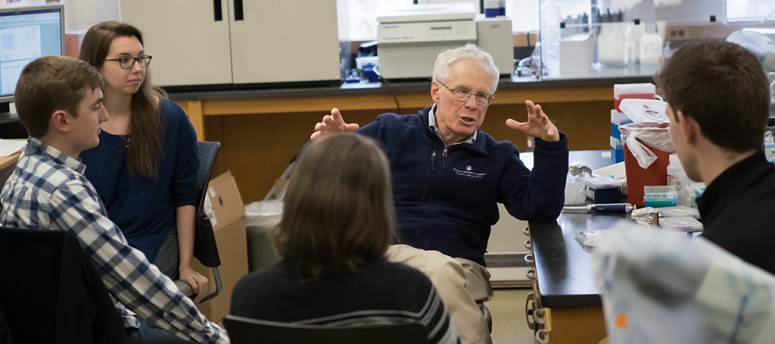

Lodish in the Lab

From Kenyon News - June 26, 2017

Harvey F. Lodish ’62 H’82 P’89 was back in a lab at Kenyon — but the tables had turned. Students eagerly explained to him their research on antibiotic resistance, as Lodish encouraged them with questions about their work.

Lodish is no stranger to engaging with budding scientists; he has taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology since 1968 and was a founder of MIT’s Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research. He relished his recent visit to the Kenyon lab of Robert A. Oden Jr. Professor of Biology Joan Slonczewski.

He also is the lead author of the textbook “Molecular Cell Biology,” now in its seventh edition and translated into 11 languages. As one of the nation’s foremost researchers in the study of cell membrane proteins, he has isolated key genes involved in hypertension and leukemia. His lab at Whitehead also studies hormones controlling fatty acid and glucose metabolism, broadening understanding of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

A Kenyon trustee from 1989 to 2007, Lodish donated $1.5 million to endow the Harvey F. Lodish Faculty Development Chair in the Natural Sciences, a professorship aimed at attracting and retaining promising young faculty members. The professorship currently is held by Andrew Engell, assistant professor of psychology.

Lodish said his support expresses his gratitude for the Kenyon education that he, his brother, Leonard M. Lodish ’65, his daughter Heidi Lodish Steinert ’89 and his son-in-law Eric C. Steinert ’89 received. One of his granddaughters will come to campus in the fall to extend the Lodish legacy.

As part of his recent campus visit, Lodish answered questions about scientific research at liberal arts colleges and his own experience as a Kenyon student.

Q: You seemed impressed during your visit with students in the lab — especially the way they now analyze data with a supercomputer on campus.

When they talked about DNA sequencing large numbers of bacteria that had certain traits, that is state of the art research. It is quite remarkable. Not every undergraduate institution would have teachers that would teach students to do that state of the art research. The computation on the supercomputer — that stuff is hard. I have graduate students and postdoctoral fellows who struggle with this kind of stuff.

The students at Kenyon are doing complicated analysis. Their data set is enormous. But they are undergraduates! What we are seeing at MIT is that students are interested in biology and computer science, and that corresponds to exactly what I’m seeing here at Kenyon. The use of giant data sets — particularly public data sets, particularly if you know what you are doing — can allow you to extract a lot of information. And these students know that this is the future.

Q: What makes Kenyon a good incubator for scientists?

It is no accident that small liberal arts colleges are generating some of the leading scientists. All the Kenyon students can communicate. I studied chemistry and mathematics and graduated in three years, but the most important class I took was freshman English. If you can read Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” you can read anything. It’s about as abstract as you can get.

Q: How has science education changed at Kenyon since you were a student?

At first, research was for just the top science students at Kenyon, then it was for all the natural science students, and now it’s becoming a part of the humanities here. We have made research a part of the undergraduate education. It transformed the education at Kenyon while keeping the liberal arts focus.

Q: What advice would you give to students who want to go from Kenyon to a research career in the biomedical sciences?

Don’t take a prescribed course. Make your own way. Take as much math and computer science as you can and don’t worry about the biology. This is what I have been saying a lot lately: Read widely, think widely and always think ahead. What are the next big problems to solve?