Recommended Reading

From The Kenyon Review - June 12, 2018

What are you reading this summer? Each year, the staff, editors, and advisory board of the Kenyon Review tell us what books they’d recommend — or are looking forward to reading themselves — as summer comes to Gambier. Here are some suggestions of books you may enjoy.

DAVID LYNN '76, EDITOR

“Burnt Shadows” by Kamila Shamsie. Shamsie, a Pakistani writer who also lives in London, opens this powerful novel in Nagasaki, shortly before its destruction. The young woman protagonist, who is one of the few survivors, leaves Japan and continues her life, forever transformed, in India, Turkey, Pakistan and beyond. This is not Shamsie’s most recent novel, but it is one of great power and lyrical beauty.

Likewise, perhaps, Kevin Young has been publishing in a variety of genres, and his most recent book of poems, “Brown,” has received enthusiastic reviews. I’ve been reading his “Book of Hours,” however, an astonishing poetic engagement with grief, loss and death. Superb and accessible poems.

Finally, the first novel by a young Kenyon author of extraordinary talent, Meghan Kenny ’96. “The Driest Season” is spare, wise, lyrical and potent. It’s a quick read and one I highly recommend.

DAVID BAKER, POETRY EDITOR

Heid Erdrich has edited a new anthology of poetry, “New Poets of Native Nations” (Graywolf), and I have been reading with deep pleasure, admiration and gratitude for weeks now. These 21 poets, all of whom published their first books after 2000, represent a dramatic sweep of styles and aesthetic tastes as well as wide-ranging tribal and Native-nation affiliations. Some may be new to you — Sy Hoahwah, for instance, or Laura Da’ — and some are more established both inside and outside of Native poetics, like Natalie Diaz, Tommy Pico and Layli Long Soldier. One of my personal favorites for years has been dg nanouk okpik, who comes from a far north Inuit village, and another is Janet McAdams from Kenyon’s own English faculty. I urge readers to find this book when it’s officially released early this summer.

I had the honor to serve as a poetry judge this year for two major book prizes, the Pulitzer Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Award, and I can’t speak highly enough of the two winners, Frank Bidart for his majestic “Half-Light: Collected Poems 1965–2016” (Farrar Straus Giroux) and Patricia Smith for her searing “Incendiary Art” (TriQuarterly Books). These are two masterful poets leading the way toward new directions in contemporary American poetry.

CAITLIN HORROCKS, FICTION EDITOR

As the title might suggest, “The Man Who Shot Out My Eye is Dead,” by Chanelle Benz, has a higher body count than most short story collections. It also has more fearless, wild ambition than most collections. The stories hop between centuries, landscapes and textual forms, and feature twisting, even shocking, plot turns.

Lisa Ko’s novel “The Leavers,” a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award, grapples with immigration and identity via a cast of memorable, vividly drawn characters. In this smart and entertaining novel, Ko extends wisdom and empathy towards every character, every predicament, every hard decision.

GEETA KOTHARI, NONFICTION EDITOR

Although Mira T. Lee writes about mental illness with great empathy and perception, I read her novel, “Everything Here is Beautiful,” as a story about home — what Lucia, one of the main characters, calls querencia, Spanish for “the place we’re most comfortable.” That search takes Lucia and her older sister, Miranda, in different directions as they both struggle to maintain their relationship, a relationship made more complicated by Lucia’s mental illness. I identified with Miranda, who feels a deep sense of responsibility towards Lucia, but in the end, I fell in love with the unpredictable Lucia. This is a beautifully written story, with unforgettable characters.

Unpredictable might also be a good word to describe the stories in Anjali Sachdeva’s debut collection, “All the Names They Used for God.” Each of the nine stories has the breadth and depth of a novel, their worlds so fully imagined and convincing that I felt like I’d walked through a door at the back of my closet and into a parallel universe. In Sachdeva’s world, anything is possible in any number of settings: the prairie, the desert in Egypt, Glacier National Park, Nigeria. In “Killer of Kings,” John Milton has help from an angel when writing “Paradise Lost,” an unlikely muse who doesn’t seem to like writers. When Milton says he needs more time, she replies, “You all say that. It’s like one unending echo down here.” Loneliness is pervasive in these pages, an underlying condition many of the characters share. Sachdeva has a gift for balancing the strange with a deeply felt sense of humanity.

SERGEI LOBANOV-ROSTOVSKY, ASSOCIATE EDITOR

As always, I’m starting the summer thinking less about books I’ve read than those I’m looking forward to reading when all the work of the semester is done. At the top of my list this year is Mohsin Hamid’s brilliant novel about refugees, exile and magical doorways, “Exit West.” I’ve recently spent some time with Ladan Osman’s poems in “The Kitchen-Dweller’s Testimony,” winner of the 2015 Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets, after hearing her give a brilliant reading here at Kenyon. I’m looking forward to spending more time with these poems when I discuss them with some Ohio high school teachers this summer. A good friend recommends Alexander Chee’s “How to Write an Autobiographical Novel,” a memoir in essays about becoming a writer. And when the hurly burly’s really done, I’m looking forward to finishing Jo Nesbø’s hardboiled retelling of “Macbeth,” set in a crime-ravaged city that evokes both early 1970s Glasgow and Shakespeare’s bloody landscape of highlands and heaths and woods that go walkabout.

As always, I’m starting the summer thinking less about books I’ve read than those I’m looking forward to reading when all the work of the semester is done. At the top of my list this year is Mohsin Hamid’s brilliant novel about refugees, exile and magical doorways, “Exit West.” I’ve recently spent some time with Ladan Osman’s poems in “The Kitchen-Dweller’s Testimony,” winner of the 2015 Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets, after hearing her give a brilliant reading here at Kenyon. I’m looking forward to spending more time with these poems when I discuss them with some Ohio high school teachers this summer. A good friend recommends Alexander Chee’s “How to Write an Autobiographical Novel,” a memoir in essays about becoming a writer. And when the hurly burly’s really done, I’m looking forward to finishing Jo Nesbø’s hardboiled retelling of “Macbeth,” set in a crime-ravaged city that evokes both early 1970s Glasgow and Shakespeare’s bloody landscape of highlands and heaths and woods that go walkabout.

KIRSTEN REACH '08, ASSOCIATE EDITOR

The early buzz for “The Incendiaries” by R.O. Kwon (Riverhead, due out July 31) is well merited, and the subject — why young people are drawn into radical acts of faith, even domestic terrorism — couldn’t be more pertinent right now. (Check out “The Stations of the Sun” in KROnline.)

Nicole Chung has been a brilliant editor for The Toast and now Catapult. Her memoir, “All You Can Ever Know” (Catapult, coming in October), is an eye-opening account of what it’s like to grow up without access to your biological family. Chung maintains a wholehearted compassion for both her biological and adoptive families’ toughest choices — and shares what it means to grow up in the space between them.

Think of the best sentence you’ve ever read and then read Jamel Brinkley’s “A Lucky Man” (Graywolf). Tell me you haven’t changed your mind.

KATHERINE HEDEEN, TRANSLATIONS EDITOR

The title of Kate Briggs’s book-length essay, “This Little Art,” refers to the often thankless, unrecognized work of the translator. An excellent and accessible meditation on the art of literary translation, it is well worth a read for those interested in understanding all that is at stake when we undervalue this essential art form.

And if you need more proof that literary translation is indeed a big, big art, A. James Arnold’s and Clayton Eshleman’s exhaustive 992-page edition of Aimé Césaire’s “Complete Poetry” does just that. The book is a tribute to one of the great poets of the 20th century, presented bilingually, and includes an introduction, chronology, extensive notes and glossary.

NATALIE SHAPERO, EDITOR AT LARGE

I recommend Tommy Pico’s “Nature Poem” and Ana Božičević’s “Joy of Missing Out,” two recent poetry collections that grapple with art, identity and public discourse in an incessantly connected world. Both poets have a lacerating sensibility and a compelling interest in skewering the expectations placed on artists and members of marginalized groups. Pick ’em up today for the ultimate anti-beach read.

I recommend Tommy Pico’s “Nature Poem” and Ana Božičević’s “Joy of Missing Out,” two recent poetry collections that grapple with art, identity and public discourse in an incessantly connected world. Both poets have a lacerating sensibility and a compelling interest in skewering the expectations placed on artists and members of marginalized groups. Pick ’em up today for the ultimate anti-beach read.

KATHARINE WEBER, EDITOR AT LARGE

A collection of four essays written more than 30 years ago, Guy Davenport’s “Objects on a Table: Harmonious Disarray in Art and Literature,” continues to offer his readers — in his words, “the common reader and intelligent children” — a beguiling and wide-ranging series of provocative contemplations that invite ways of seeing patterns of culture just as we more typically recognize patterns of nature.

Though it won’t be published until September, it’s not too soon to look forward to Kate Atkinson’s new novel “Transcription,” a return to the rich territory of wartime London. When Juliet Armstrong is recruited for unusual espionage work that turns out to be “more than a bit of a lark,” it becomes a way of life that suits her almost too well. Though a bit less layered than “Life After Life” or “A God in Ruins,” it’s got the trademark Atkinson blend of subtlety, wit and several kinds of unexpected turns.

MAGGIE SMITH, CONSULTING EDITOR

This summer I’ll continue to work through the teetering stack of poetry books in my living room, including Bill Knott’s “I Am Flying into Myself: Selected Poems, 1960–2014,” which I’m loving as much for the poems’ unabashed tenderness as for their idiosyncratic rhetorical stances.

A poem is a room that contains

the house it’s in, the way you

accommodate me when I lie

beside you, even if the address

is lost so many times and the names

of streets and strangers that pass

shuffling a card-deck of maps

whose rubberband has snapped . . .

I also highly recommend Anna Rose Welch’s “We, the Almighty Fires” (Alice James Books) and Jenny Xie’s “Eye Level” (Graywolf), two of the finest first books I’ve ever encountered.

MISHA RAI, KENYON REVIEW FELLOW

I want to recommend two novels: “When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife” by Meena Kandasamy and “What We Lose: A Novel” by Zinzi Clemmons. Both of these books are beautifully written, important to the social and political conversations taking place globally, and generally a gripping read.

I want to recommend two novels: “When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife” by Meena Kandasamy and “What We Lose: A Novel” by Zinzi Clemmons. Both of these books are beautifully written, important to the social and political conversations taking place globally, and generally a gripping read.

ANNA DUKE REACH, DIRECTOR OF PROGRAMS

“Less” by Andrew Sean Greer. Arthur Less, a washed-up writer turning 50, decides to accept invitations to lesser literary events to avoid the humiliation of attending his ex-boyfriend’s wedding. This hilarious odyssey of disasters is a fun (and Pulitzer Prize winning) summer read, especially for writers.

“Calder: The Conquest of Time, The Early Years, 1898–1940” by Jed Perl. A detailed biography of Alexander Calder’s playful genius and his monumental influence on modernism. Perl emphasizes that Calder’s roots in the Arts and Crafts Movement plus his deep appreciation of everyday objects (such as children’s toys) combined to make him a superstar sculptor. Perl’s literary portrait describes a Calder stabile as having “the spiderweb strength and delicacy of an Emily Dickinson poem.” This is the first half of the biography; the second half is anticipated in 2019.

ELIZABETH DARK, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF PROGRAMS

Joy Williams’s short story collection, “The Visiting Privilege,” brings together 50 years of her thoroughly brutal and humorous analysis of the American experience. Together, her sentences and her characters expose our capacity to be cruel, our inability to hold it together and our frustrating tendency to die. Reading this collection leaves us laughing at and reckoning with ourselves, all in one go.

Hanif Abdurraqib’s collection of essays, “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us,” demonstrates the insight and wisdom that can come from merging music writing, cultural criticism and poetic flair with personal narrative. Abdurraqib ties our country’s fraught history and questions of being to each of the encounters he explores, be it a song lyric, a concert crowd or a news cycle. When he asks, “What good is endless hope in a country that never runs out of ways to drain you of it?” he extends to us the invitation to partake in the answer.

DAVID BERGMAN, ADVISORY BOARD

Andrew Sean Greer’s “Less” is the rare comic novel whose complexity is worn lightly enough that you can bring it to the beach in comfort or take home in satisfaction. Li-Young Lee’s new volume of poetry, “The Undressing,” is exactly the opposite of what the title suggests. These poems are not stripped down to the bare essential but allowed to expand sometimes beyond their breaking point. But what glittering shatters he leaves us!

Andrew Sean Greer’s “Less” is the rare comic novel whose complexity is worn lightly enough that you can bring it to the beach in comfort or take home in satisfaction. Li-Young Lee’s new volume of poetry, “The Undressing,” is exactly the opposite of what the title suggests. These poems are not stripped down to the bare essential but allowed to expand sometimes beyond their breaking point. But what glittering shatters he leaves us!

NANCY ZAFRIS, ADVISORY BOARD

Surely one of the best novels of the year is “Winter Kept Us Warm” by Anne Raeff. The story spans six decades and three continents. It opens in postwar Berlin, where Ulli, a young German woman, engages in funny and subversive translations for GIs hoping to flirt with German girls. There in the bar she meets Isaac and Leo. The novel ends six decades later in Morocco, in a hotel Ulli now runs and where Isaac has come to see her after 40 years (and after raising her two daughters by Leo). A profound meditation on love, commitment and personal fulfillment, the novel displays an exhilarating intelligence that matches the delights of the complicated plot.

Surely one of the best novels of the year is “Winter Kept Us Warm” by Anne Raeff. The story spans six decades and three continents. It opens in postwar Berlin, where Ulli, a young German woman, engages in funny and subversive translations for GIs hoping to flirt with German girls. There in the bar she meets Isaac and Leo. The novel ends six decades later in Morocco, in a hotel Ulli now runs and where Isaac has come to see her after 40 years (and after raising her two daughters by Leo). A profound meditation on love, commitment and personal fulfillment, the novel displays an exhilarating intelligence that matches the delights of the complicated plot.

JOANNA KLINK, WRITERS WORKSHOP INSTRUCTOR

I picked up John Williams’s “Augustus” because I wanted to better understand the history of Rome — and because the Washington Post quote on the jacket cover was “The finest historical novel ever written by an American.” I was blown away by this book. If you’ve ever read “Stoner,” you know that Williams is a quiet, hypnotic writer, attentive to human vulnerability and pride, to the vast sorrows a single person can shoulder. Augustus fuses Williams’s psychological insight with the blazing plot of Octavian’s rise, from a shy teenager to the first Roman Emperor — at brutal costs. Structured as a series of intimate letters from different characters, the novel tracks evolving events; you step into the minds of, among others, Cicero, Brutus, Mark Anthony, Cleopatra, Livia, Virgil and Horace. The book is also a wrenching portrait of Augustus’ daughter Julia, and the disillusions that compel father and daughter to act against their own loves.

I picked up John Williams’s “Augustus” because I wanted to better understand the history of Rome — and because the Washington Post quote on the jacket cover was “The finest historical novel ever written by an American.” I was blown away by this book. If you’ve ever read “Stoner,” you know that Williams is a quiet, hypnotic writer, attentive to human vulnerability and pride, to the vast sorrows a single person can shoulder. Augustus fuses Williams’s psychological insight with the blazing plot of Octavian’s rise, from a shy teenager to the first Roman Emperor — at brutal costs. Structured as a series of intimate letters from different characters, the novel tracks evolving events; you step into the minds of, among others, Cicero, Brutus, Mark Anthony, Cleopatra, Livia, Virgil and Horace. The book is also a wrenching portrait of Augustus’ daughter Julia, and the disillusions that compel father and daughter to act against their own loves.

E.J. LEVY, WRITERS WORKSHOP INSTRUCTOR

I recommend Tayari Jones’s wonderful novel, “An American Marriage,” about a marriage torn apart by the new Jim Crow, and Graham Greene’s delightful portrait of toxic doubt, “The End of the Affair.” Watch for Maureen Aitken’s heartbreaking collection of linked stories, “The Patron Saint of Lost Girls,” winner of the 2016 Nilsen Literary Prize, which reveals the numinous beauty in ordinary lives. With uncommon grace and wit, Aitken vividly evokes Detroit, the industrial Midwest and a nation at a moment of transformation and trial, in which lives are ultimately redeemed by small acts, enduring love and language. An anthem for a post-industrial Midwest, an America shifting beneath these characters’ lives, these wonderful stories attest to damage done and to the power of art and language to revive. “Nothing good was a straight line,” one character observes. “What was beautiful knew how to veer on a whim.” Wonderfully, these stories do.

I recommend Tayari Jones’s wonderful novel, “An American Marriage,” about a marriage torn apart by the new Jim Crow, and Graham Greene’s delightful portrait of toxic doubt, “The End of the Affair.” Watch for Maureen Aitken’s heartbreaking collection of linked stories, “The Patron Saint of Lost Girls,” winner of the 2016 Nilsen Literary Prize, which reveals the numinous beauty in ordinary lives. With uncommon grace and wit, Aitken vividly evokes Detroit, the industrial Midwest and a nation at a moment of transformation and trial, in which lives are ultimately redeemed by small acts, enduring love and language. An anthem for a post-industrial Midwest, an America shifting beneath these characters’ lives, these wonderful stories attest to damage done and to the power of art and language to revive. “Nothing good was a straight line,” one character observes. “What was beautiful knew how to veer on a whim.” Wonderfully, these stories do.

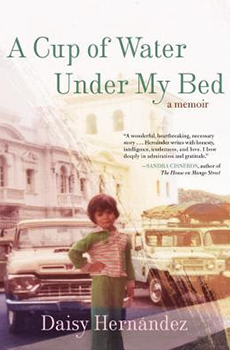

DINTY W. MOORE, WRITERS WORKSHOP INSTRUCTOR

As the genre of literary or creative nonfiction continues to evolve, one intriguing trend is the blending of memoir and personal essay into books that bring us into an author’s life while simultaneously offering fresh takes on identity, sexuality, ethnicity and race. (Yes, James Baldwin did this decades ago, but what’s old becomes new again.) In “A Cup of Water Under My Bed,” Daisy Hernández offers a compelling, compassionate look into the immigrant experience of her Colombian-Cuban family and her own struggles to negotiate disparate worlds. In the inventive “Buddha’s Dog & Other Meditations,” Ira Sukrungruang ponders his dog, his large body and his Thai heritage with humor, grace and disarming honesty. And in “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us,” Hanif Abdurraqib turns what is ostensibly a book of music reviews into a powerful meditation on culture, celebrity and the perils of being black in America. I recommend reading these back-to-back, or together.