Mysteries of the Universe

From Kenyon News - October 4, 2016

Two Kenyon faculty members number among the more than 1,000 scientists who contributed to the project that won the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics.

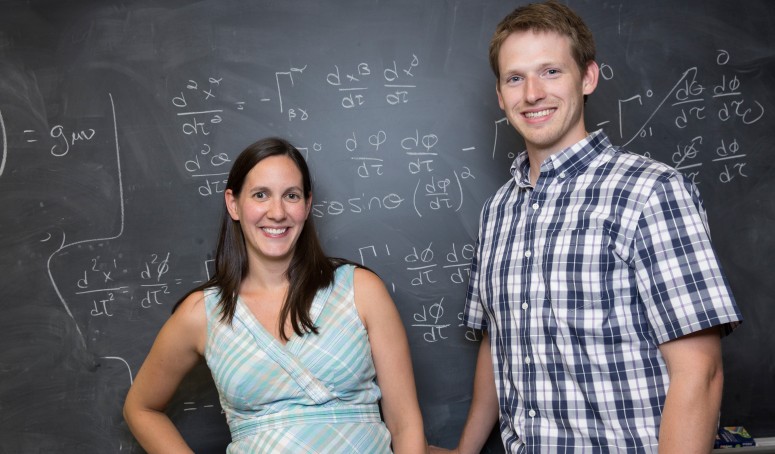

Assistant Professors of Physics Leslie and Madeline Wade are members of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) Scientific Collaboration, a worldwide group that made a splash in February 2016 with the announcement of its historic detection of gravitational waves caused by two black holes colliding. The news confirmed the existence of gravitational waves, which had previously only been predicted by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Three leaders of the LIGO project, Drs. Rainer Weiss of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Barry Barish and Kip Thorne of the California Institute of Technology, were announced as the prizewinners in Stockholm on October 3.

“We have telescopes to detect all sorts of things coming from outer space,” Leslie said. “Now we have access to a new type of wave that sends information about sources that is typically very complementary to light. So we’ve opened up a new way of looking at the universe. We expect to see things that were invisible before.”

LIGO uses lasers on a large scale to detect gravitational waves, or ripples in space-time, caused by cosmic events such as black holes colliding or neutron stars merging. The collaboration has installations in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, and plans are underway for an installation in India.

“We only ever had been able to gather information about the universe by using light, and now we have a different method for that,” Madeline said. “The immediate application use to one’s everyday life is maybe not completely clear, but neither was the invention of quantum mechanics to give you your cell phone. It’s a new field and a new era, and therefore there will be new results. What those are is yet to be discovered.”

The Wades first became involved with LIGO seven years ago in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where they applied under the advice of Associate Professor of Physics Tom Giblin, who was teaching at Bates College at the time and had advised the Wades on some of their undergraduate research. After graduating, they searched for teaching positions where they could empower students to join the LIGO collaboration, and Kenyon hired the couple in 2015.

The Wades tackle two ends of the LIGO research pipeline. Madeline focuses on calibrating the interferometer and preparing its data output for analysis. Once the data is prepared, Leslie uses it to search for gravitational waves and decode the information carried in the waves to learn more about neutron stars and black holes, which can be difficult to detect through other types of telescopes.

“Black holes are notoriously hard to find because they don’t emit any light. Instead, you can infer their presence through their gravitational effect on nearby bodies,” Leslie said. By observing gravitational waves, scientists also will learn more about the structure of the universe and black hole and neutron star formation rates.

Helping them with their research in Gambier is a handful of students eager to be part of their groundbreaking team.

“I think it’s a great success of how one of these cutting-edge experiments can integrate itself into a place like Kenyon,” Giblin said. “Les and Maddie have done such a wonderful job integrating the best aspects of the collaboration — the opportunities and the money and the projects — and bringing that on campus here and encouraging our students to make that part of their physics major.”

One of their students, Tracy Chmiel ’17, a physics major and mathematics minor from East Amherst, New York, knew about the Wades’ work even before they arrived at Kenyon as professors. In her sophomore year, with the help of Giblin, her advisor, Chmiel emailed Madeline asking if she would be interested in working together on an independent study project. Two independent study projects and a Summer Science research experience later, Chmiel became engrossed in work with LIGO and tackled a senior honors thesis focusing on aspects of the interferometer’s calibration.

“It’s a really great community, and it’s a really great workspace,” Chmiel said about the LIGO group at Kenyon. “The physics department is really good at giving you spaces to work together, and that’s what the lab feels like.” Chmiel is now continuing her study of physics at the University of Chicago.

The Wades are working to open up research opportunities to even more students. They have brought the Aerocibo Remote Command Center (ARCC) program to Kenyon, which allows undergraduates — even those who have never taken a physics class — to remotely control two of the world’s largest radio telescopes in West Virginia and Puerto Rico to observe pulsars, or rapidly rotating neutron stars that regularly emit beams of radio waves. The information collected from the students’ pulsar exploration can be used to search for gravitational waves.

“It’s a big responsibility, but Kenyon students are ready for it,” Leslie said.

Ultimately, the Wades have a whole universe left to explore through LIGO.

“I’m excited to start seeing more of the universe, because I don’t know what’s out there, and we’re about to find out,” Madeline said. “That’s pretty cool.”