Moss Possibilities

From Kenyon News - December 21, 2015

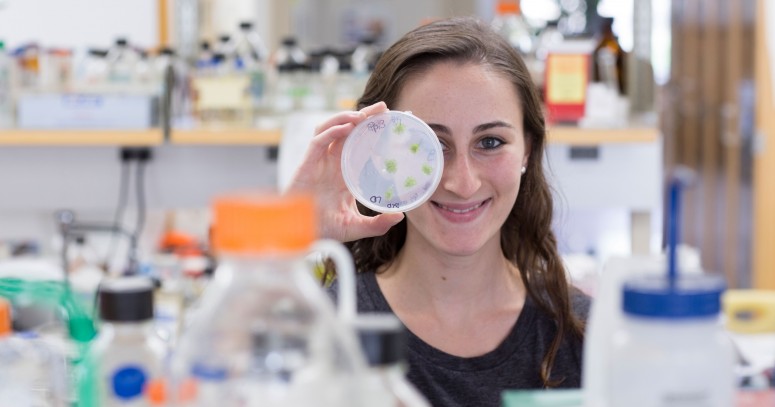

With an American Society of Plant Biologists (ASPB) grant, Maria Sorkin ’16 grew moss from spores in petri dishes this summer, plucking bits for hundreds of test tubes and measuring how different genes affect the plant’s reproductive cycle.

The biology major from Pittsburgh was one of 15 students to win the association’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship, open internationally and known as the SURF award. Sorkin’s work is one piece of long-term studies by Associate Professor of Biology Karen Hicks about how plants sense seasonal cues and whether that sense is ancient and evolved before flowering plants and moss diverged 500 million years ago.

Sorkin is Hicks’ second student to secure a SURF award, which is meant to encourage interested students to go into plant science. “That’s really her passion. And that’s whom the association awards: people who have that passion,” Hicks said.

Sorkin specifically is studying genes associated with the circadian rhythm, an organism’s responses to light and dark throughout the day. She will continue growing and testing the moss throughout the school year, planning to write her thesis for the Honors Program in biology about the research.

The ASPB will pay for her to attend its conference this summer in Austin, Texas, to present her work with other fellowship winners. The award has put her in an elite pool of plant biology students, Hicks said, noting that top doctorate programs already are contacting her to apply.

Her project was part of the Kenyon Summer Science Scholar program, but once she learned that she earned the $4,000 national stipend, her award from Kenyon was freed up for another student researcher.

Similar studies have been done widely on more complex flowering plants, helping farmers optimize planting times. Sorkin grows the moss until it develops tiny brown nodules of spores, the plant’s reproductive method that evolved as water plants moved onto land, she said. “It’s a good starting point for an evolutionary study,” she said of the species that she tests.

One benefit of working with moss is that its entire set of DNA has been sequenced, a project that Hicks helped complete with many scientists about a decade ago. Sorkin said knowing the location of all the genes makes amplifying one for testing easier.

In Hicks’ lab, Sorkin adjusts the temperature and light levels to cause the little clumps of moss to reproduce. “Under the direction of this internal clock that is harmonized with its environment, plants are able to decisively begin reproductive development at the appropriate time of year, thereby outcompeting those individuals that are not primed for this critical life event,” she wrote in her poster about the project that she presented with other summer scholars at a symposium during Family Weekend.

Outside the lab, Sorkin loves her job as a senior consultant for campus technology helpline, training other student workers. She also interns with the K-STEM program that organizes mentoring and workshops in STEM fields: science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Sorkin, who is applying to graduate schools, became interested in an industry career related to plants after visiting a biotech company during a 2014 summer research internship at North Carolina State University. “I kind of thought, oh, this is what people do with plant biology, and I got a taste of what grad school would be like, which is working full time in a lab. It was a lot of fun. I loved it.”

She came to Kenyon knowing she liked biology, but her interest turned to plants partly because “a lot of the professors I’ve had here at Kenyon are great plant biologists.” And she clearly prefers studying plants to human ecology or research on animals. “Plants are much easier to work with than animals. They just kind of stay put, don’t ask for anything. They’re easy to take care of.”